Written by Ruixuan Li – Dec 2014

Presented at the Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco, the solo exhibition Promises to Pay in Solid Substance (September 5 – November 1, 2014) by the Brooklyn-based, emerging Canadian artist Hugh Scott-Douglas, includes three new bodies of work: Economist (2014), Amazon.com (2014), and Heavy Images (2014), and one of his older works, entitled Screentones (2014), which first appeared in Takashi Murakami’s exhibition space in Tokyo. Curated by the gallery’s owner Jessica Silverman, the exhibition comes with an informally printed “zine”, which includes an essay written by Hugh Scott-Douglas, downloadable as a PDF file from the gallery’s website. By assembling technology-related objects into this exhibition, Scott-Douglas’ latest works create a conversation around the relationships between digital and analog forms, within contemporary life and in particular the economy today. In this discussion, I reflect on how the works complicate some of these relationships and how the relationships might be changing over time and within different contexts. One might argue that this project demonstrates that value and meaning in a digital or analog world depends on time and background.

Presented at the Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco, the solo exhibition Promises to Pay in Solid Substance (September 5 – November 1, 2014) by the Brooklyn-based, emerging Canadian artist Hugh Scott-Douglas, includes three new bodies of work: Economist (2014), Amazon.com (2014), and Heavy Images (2014), and one of his older works, entitled Screentones (2014), which first appeared in Takashi Murakami’s exhibition space in Tokyo. Curated by the gallery’s owner Jessica Silverman, the exhibition comes with an informally printed “zine”, which includes an essay written by Hugh Scott-Douglas, downloadable as a PDF file from the gallery’s website. By assembling technology-related objects into this exhibition, Scott-Douglas’ latest works create a conversation around the relationships between digital and analog forms, within contemporary life and in particular the economy today. In this discussion, I reflect on how the works complicate some of these relationships and how the relationships might be changing over time and within different contexts. One might argue that this project demonstrates that value and meaning in a digital or analog world depends on time and background.

Scott-Douglas’ work Economist consists of six enlarged magazine photographs that the artist reprocessed and printed onto wood panels. These hang on the walls of a white-cube gallery space independently or in pairs with three photographs from another series Screentones. For the latter work, the artist applied the adhesive and transparent letratone sheets to multiple surfaces in his studio, and then sampled the dust and tiny debris of this practice to the scanner and printed them onto wood panels. In another corner, ten pieces that make up the work entitled Amazon.com hang in panels that stand out from other works on the walls because of their use of mixed materials such as prints, frames, polyester, and tape. If Amazon.com occupies the walls of the gallery, Heavy Images takes over its floor space, containing boxes and rolled-up billboards spread out over the surface of the boxes. According to the show’s exhibition brochure, Heavy Images is “made from large-scale expired billboard prints acquired online after they had served their commercial use.” Therefore, the originally discarded shipment cases and billboard prints are now on display in the gallery as artworks following the artist’s use and re-framing of these materials.

According to Jessica Silverman, most of the exhibition’s ideas came from the artist: “I also wanted to give him his own space to make the choices he wanted… He was fairly confident in how he wanted the show to look because he had visited the space many times.” Silverman’s methodology agrees with the curator, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s idea of exhibition as a venture that allows artists to parody, undermine or depict cultural assumptions through their works. For Christov-Bakargiev, each new exhibition can be a laboratory that informs strategies for new discourse of standards. Likewise, this show, Promises to Pay in Solid Substance, strongly conveys Scott-Douglas’ voice to the audience. He uses various high techniques to rethink digital culture’s influence on people’s lives, which, according to the critic Karen Archey, is under the category of “Post-Internet art”. Archey gives a definition of this new term in her essay, Postinternet Observations, saying that “the ‘post’ here refers not to ‘coming after,’ but rather, ‘in the fashion of.’ [It describes] a moment in which the internet is no longer a fascination or taboo, but rather a banal fact of daily living. ‘Postinternet’ should be considered a cultural condition.” It is also concluded by the art writer, Brian Droitcour that “unlike ‘Neo-Expressionism’ or ‘Neo-Geo,’ ‘Post-Internet’ avoids anything resembling a formal description of the work it refers to, alluding only to a hazy contemporary condition and the idea of art being made in the context of digital technology.”

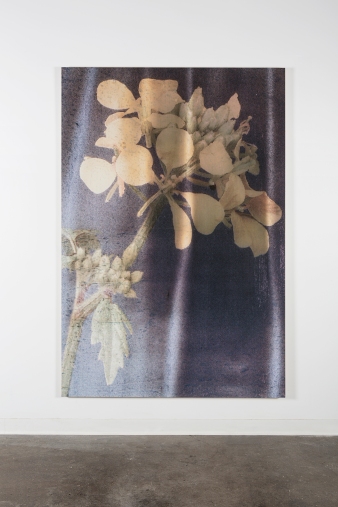

One of Scott-Douglas’ previous exhibitions, called A Cashed Cheque, a Canceled Stamp talked about such a “context”. This exhibition was also presented by Jessica Silverman Gallery from December 2011 to January 2012. It showcased an exquisite series of cyanotypes on linen, the textile of which was impregnated with a light sensitive emulsion and exposed to natural light. Another series of laser cut on linen was also on display, where each composition was developed from photographs of earlier pieces, recording the trace of its earlier printing. Of these woks Scott-Douglas writes “each work ends up being recycled over and over again, and is stored in a digital archive, it allows for the potential to be realized repeatedly.” Thus, the images demonstrate digitalized instances of the physical changes that occur across the production of his works. In the “zine” for Promises to Pay in Solid Substance, the artist writes “Once form is separated from matter, through the transformation of solid substance into its image on a negative, the image can be transferred in efficient, low-friction movements through networks of display and consumption.” Here, Scott-Douglas emphasizes that the separation of physical photographs from digital files contributes to the images’ circulation. He also mentions, “In the same way that currency has become dissociated with the reality of the gold reserve, so have (digital) photographic outputs become wholly separated from their material foundations,”7 further highlighting his argument that both “digital image – material photos” and “monetary value – currency or coins” share a separated state under the Post-internet environment. However, what are the deeper effects on both sides of this coin (of physical material and digital information) after the separation?

Looking back at Economist series, Scott-Douglas transferred the images by applying many layers of a clear acrylic gel to the printed page, then scanned the transparent transfers, magnified them and baked the images onto wood panels using UV-curable ink. These works are in line with the post-Warholian style of ready-made imagery, and its replicating process may lead the audience to think about the issue of authorship and ownership through copying and batch production. Andy Warhol’s screen print works such as Marilyn Diptych (1962) include fifty images of Marilyn Monroe based on a single publicity photograph from the film Niagara (1953), where each iteration expresses a different color quality or registration. Like Warhol, artists today such as Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami can make multiple copies of art, but can do so at much more accelerated rate than Warhol had made his prints. Hal Foster critiques in his article “The Medium is the Market” that “Koons oversees a studio factory with some ninety employees in Manhattan, while Murakami runs a corporation with seventy employees based in Tokyo and Queens. Work signed ‘Koons’ or ‘Murakami’ is largely designed on computers by assistants and then executed by fabricators.” Thus, with computer software, copying has grown with leaps and bounds.

A group of art historians dispute that such accelerated copying has put authorship and ownership under severe threat. In their article “Something from Nothing: How Digital Art Recreates the Image,” two professors from University of Calgary, Jennifer Eiserman and Gerald Hushlak declare that “the serialization of the printing press and the ‘objective’ means of image capture of photography meant that images could be translated from one form to another, could be created in numbers so vast that they had little economic value as exclusive objects.” In other words, as the techniques evolved, reproductions of artworks could be widely disseminated, and they emerge as substitutes of the original and devalue with each subsequent derivative. However, in Koons’ and Murakami’s current cases of manufacturing multiples, copying is more their art-practice than a technique. Paradoxically, by selling these copies, these two artists are making a fortune, which shows an example of the changing value of reproductions.

In the exhibition display, the Screentones installed close to the Economist series, act as a supplementary of the topic of derivatives. The enlarged images hanging on the gallery’s wall are derived from the copies of the dust and small debris in the artist’s office. They were created so easily that the audience may question whether the digitalized and reframed images can be viewed as artworks. This art production shows a simple “from trifles to art” derivation alluding to the controversial derivative works and even that gift developers buy the copyright from artists to make art commodities. A classical example is Takashi Murakami as mentioned by Hal Foster: “His (Murakami’s) biggest splash in the West came in 2002 when Marc Jacobs commissioned him to design a version of Louis Vuitton monogram; sales of handbags with the rebranded symbol exceeded $300 million in their first year of production.” Such “art crossover fashion” or “art crossover gift” creates miracles that now frequently occur in the luxury market. When looking at the whopping prices of the art commodities, one might doubt that the artworks’ images really bring the artistic value and investment value to the products. Are the commodities in the artworks’ skins also collectable objects?

Such doubts of value exist everywhere, especially in the highly-developed and sophisticated financial market. Since asset prices have risen incredibly high above their underlying value; the value of financial products has been increasingly questioned since the 2008 stock market crash. The financial institutions derived the now-infamous credit-default swaps (CDSs) from subprime mortgages, and CDSs initially offered attractive rates of return due to the high interest rates on the mortgages. After being inflated for a long time, the housing bubble finally burst and broke the capital chain of the mortgage, which caused the subprime crisis. René M. Stulz, professor of finance at Ohio State University, concludes that the 2008 subprime mess has triggered the most destructive financial crisis since the stock market crash of 1929. Subsequently, the financial derivatives in general and credit derivatives in particular are undisputedly labeled “financial weapons of mass destruction.” From this painful lesson, many people in the financial industry also judge the worth of investing financial derivatives, just like art collectors may worry that their investments in art commodities will decrease in value like the housing bubble and whether or not art is worth investing in.

The two informative works, Economist and Screentones, illuminate the topics of copying and derivatives, and furthermore illustrate materials and information’s periodical changes in their value and meaning. The art writer Francesca Sonara writes in her review: “Before being printed onto the panels, the dust bunnies and journalistic sources were scanned, mapping a circuitous route wherein the tangible begets the digital begets the tangible”. Here, Sonara claims that the development of the images makes a circuit connecting physical material to digital image and then to physical prints. The artwork Heavy Images in some ways restates this type of chain of events which includes different phases. First, the images were weightless TIFF files. When converted to print, they were made into the billboards with physical weight as material goods and commercial value in relation to the business of advertising. When the banners were displayed as advertisements to target customers, it had economic promotional value. As time went by, the events or promotions shown on the billboards ended, therefore the billboards lost this value. Now, these billboard prints along with discarded shipment cases were displayed in the gallery as artworks following the artist’s use and re-framing of these materials. One can see that the billboards have gone through many phases, and each phase acts as a template for its “evolution”.

Another work—Amazon.com—further discusses the phased “evolution”. For this work, Scott-Douglas took blind snapshots of overflow Amazon packages in the hallway connected to his Brooklyn studio, which connects to one of the company’s distribution centers. He then printed and framed the photos, and wrapped and taped them with the same packing supplies as are visible on the shipments in the photos. In the exhibition, the works’ shapes mimic their contents: i.e., the treatment of framing and wrapping of the displays parallels the contents of photographs in which the displays emerge in a mirroring experience. Through this frame-within-frame structure, the frames and wraps symbolize another layer of packaging taking place outside of real Amazon packages, and similar to Amazon’s trucks. The structure also implies that the commodities themselves may be carrying things, which could be the aesthetic value or an exclusive memory. As the critic, Georg Simmel claims that “nowadays what buyers pursue from an object is the great pleasure or advantage they experience a feeling of joy at every later viewing of the object.” The customers’ needs of pleasure drive them to browse Amazon.com, and then they are attracted by the digital images of commodities. Once payment is made, the commodities are physically dragged to be packaged and, transportation is requested for delivery. This process builds a rewards system without regarding to the monetary value. It is the nonmonetary value that transfers an ordinary item in the warehouse into a meaningful reward and pulls all the substances to make up a supply chain.

As analyzed above, Hugh Scott-Douglas’ works probe the interconnection as well as the departure between tangible materials and the digitalized data of the Internet. The three major relationships are: digital copying, derivatives from the original works, and the periodical developments in value and meaning of both copying and derivatives (a good example would be Post-Internet art currently linking artworks with the Internet). Even been defined here, the relationships keep changing depending on time and contexts. “Post-Internet” is a neologism, while the network and technologies have been playing roles in art practice for more than 20 years. A recent forum was organized by Frieze Magazine to let eight artists, writers, and curators reflect on their thoughts about Post-Internet art. Hanne Mugaas, the director of Kunsthall Stavanger, says that “let’s not forget those long-ignored histories of media art and net.art. Afterall, 1990 net.art taught us about the possibility of having meaningful art experiences through our browsers.” Corresponding with Mugaas, Lauren Cornell also talks about the different net-related art forms: “Much net.art took place online …, ‘Post-Internet’, on the other hand, seems to demarcate work that exists within a gallery but which has a relationship to a broader set of cultural conditions influenced by the web.”17 By saying this, she points out the developmental meaning of “Post-Internet art” as one that is not a form, whereas the previous art forms treat technology as a media or platform. “The way we access and circulate information has changed profoundly, as have our behaviors and, arguably, even the way we think,” 17 Cornell states. For instance, Katja Novitskova is a Post-Internet artist based in Amsterdam. For her, the Internet is a tool, while her media is the netizen’s attention. A New York-based writer Tyler Coburn values Novitskova’s works as utilizing attention as a commercialized material. Coburn thinks that artists like Novitskova anticipate a full-on attention economy to monetize one portion of the extensive free work they perform for their virtual service providers. Therefore, according to Coburn, attention is fast becoming a popular but deficient resource. 17 This conversation reveals the Internet’s role-shifting and the significance of the attention economy on the web, which has become an influence on contemporary artists. What’s more, the attention brings not only reputation but also authenticity to the artists, which acts as a new art media.

Hugh Scott-Douglas’ Promises to Pay in Solid Substance, like the other exhibitions that popped in Jessica Silverman Gallery and discussed about the technology’s effects on people’s lives, brings the progressive ideology up again to the audience. Apart from leading the viewers into a discourse of the relationships between materiality and immateriality, the artist displayed the leftover materials from the value-changing processes as records by which people can trace the changes. Also, his actions of adding new value concepts have provoked people to think in a broader view. Would such adding-value actions inspire novel products in the future economy? In the running chains of commodities or money, resources sometimes turn to wastes due to operation needs, thus, taking measures to recycle them would be a new direction of economic development.